For anyone who has lived abroad for at least a year, you know full well that desperate times call for desperate measures. And sometimes, it takes a lot to get used to your new surroundings--new language, new cultures, new fads, and new no-nos. In America, it might be safe to drink tap water but in other parts of the world, you might as well sign your own death sentence. Here in Bayannur, we wash our clothes by hand and we have to wait for the sun to heat up the water for our showers (that took us way too long to figure out!).

The life of a traveler is filled with adapting to new cultures... but there are some things that I find I just CANNOT give up, no matter how many places I've traveled or how hard I try to assimilate into the culture I live in.

Most times, you cannot easily find the things you love, celebrate, or crave... so it's up to you to get your hands dirty, get a little creative, and do it yourself!

Holidays

Holidays are always the toughest to try and celebrate when you're living in a country so different from your home. China is a perfect example. Staple holidays like Christmas, Thanksgiving, and Halloween do not exist over here and if it does, that's because tenacious expats make sure to find ways to celebrate.

Thanksgiving is easy enough to work with--you might have to eat chicken instead of turkey. One year I made chicken wing dip but couldn't find bleu cheese dressing so I had to go with "yoghurt dressing" whatever the hell that means. It turned out okay to the untrained laymen but Adam and I could taste the difference and it was unacceptable.

|

| Those roots are unacceptable too... |

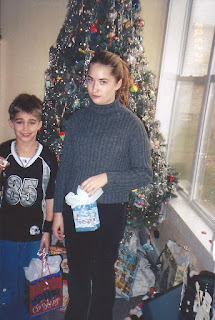

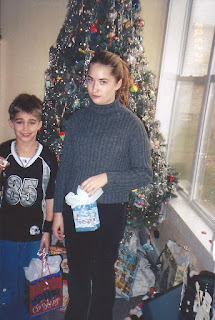

Christmas is pretty popular in China. As a matter of fact, some stores are STILL decorated. The only aspect of the holiday that I find a bit disappointing in the fact that it somehow hasn't made it's way over to China is the elusive pickle! It's a German tradition and one that my family has always celebrated. I won't go into the fact that for almost two decades Jed would destroy me... I don't think I ever actually found the pickle.

|

| Back when I was actually taller than Jed. Moody teenage Amanda with her itty bitty prize and adorably awkward Jed with the pickle and his stupid big prize. |

For those of you unfortunate souls who are neither German nor celebrate Christmas with the pickle, let me explain. Traditionally, the glass pickle is the last ornament to go on the Christmas tree and the child who is the first to find it gets an extra gift on Christmas Eve. Today, kids strangle and wrestle one another to try and get to the tree first. I've done this all my life and not once have I succeeded.

In China, it's a bit difficult to find a glass ornament in the shape of a pickle (shocking, I know!). So, one Christmas, while in China, Adam and I decided to improvise. Instead of a pickle we used a pepper... a real pepper.

It's Halloween that's the tough one to still find a way to celebrate, no matter where you are. Halloween is a sacred holiday for me, and so, no matter where I am--China or Russia it would seem--I find a way to celebrate.

In China, I managed to carve a jack-o-lantern out of a watermelon (you can read more about that

here) and somehow it actually turned out awesome! That same year, I was able to introduce the art of pumpkin (watermelon) carving to my students at an English corner. They were able to realize just how much they were missing out in the glorious month of October.

It was interesting to find in Russia, too, Halloween is not nearly as popular (or at all) as in America. Actually, Putin has tried to outlaw public displays of Halloween frivolity in big cities such as Moscow and St. Petersburg because he sees it as a negative Western influence, particularly coming from America. However, Novosibirsk is far away (I mean FAR away) from Moscow and so Halloween is a bit more accepted in the city. We actually had some Halloween parties with students and some teachers even dressed up.

Luckily for me, I was off on Halloween and had all day to celebrate. But once again, it was impossible to find pumpkins to carve! It was like China all over again. Instead of watermelons, we decided to actually buy gourds and carve them into jack-o-lanterns. I think there's a reason why pumpkins were chosen for carving (contrary to what you might think when you're trying desperately to carve a circle into a pumpkin)--they're easy to work with! At least easier than the evil gourds we picked.

FOOD

Now, a good traveler is one who is always brave and willing to try new foods and be content with eating the foods of the country they are visiting or residing in whether it's rice and noodles or cabbage and vodka. However, being content with what your specific country has to offer you can only last for so long and eventually the cravings begin to set in. Usually this is once the "wonderment" phase of culture shock passes and you suddenly realize you have absolutely no access to good beer, huge hunks of meat, or cheese. It's about one month in that rice, noodles, and vegetables just aren't good enough anymore and these cravings usually start. And it is at this time that--in order to survive--you must take matters into your own hands.

I've found that DIY food projects can either turn out really good or really really bad.

The Good: Chicken wings

For my 24th birthday, instead of going out to a fancy restaurant in Hangzhou, I wanted to attempt #139 from My Life List (you can read all about our kitchen escapades right here). And so with a bottle of Frank's and 25 chicken wings from the wet market, we attempted and--I'm proud to say--succeeded in making chicken wings that were good enough to appease this Buffalo girl.

The Bad: Mulled Wine

For every success in the DIY expat collection, there has to be an utter failure and that would be our attempt at hot mulled wine for Christmas 2013. We figured we had cinnamon sticks, an orange, and come cloves--why not throw it in and heat up some of our leftover Chinese red wine? SUGAR. No one told us to add sugar. So, no surprise, it was terrible. We've gotten better at it! But I suppose we had nowhere to go but up.

We've done a few other DIYs over the years. Christmas ornaments, attempts at making bacon only to realize you bought pork organs and not pork, baking brownies from hot chocolate packets when you don't have cocoa powder, making olive brine by adding saltwater to your olives for the perfect martini, and building furniture out of scraps of wood you find lying against the garbage shoot (this totally worked but sadly we have no photos which is a shame!).

This past week, we've continued on in the DIY tradition by successfully making two things of food (you can clearly see that most of this post is about food... mainly because I'm hungry at the moment): homemade jiaozi 饺子 (basically dumplings you can boil, steam, or fry) and cheese!

Jiaozi 饺子:

I am a big fan of jiaozi. Ever since moving to China, they are some of my go to meals. In Hangzhou, they were usually beef or pork but here in Bayannur, most of them are mutton (Yang Rou 羊肉). Around here, they seem to be steamed usually which is fine but sometimes you just want something unhealthy and fried... and that's just what we did.

Taking what little mutton we had left from our Easter celebrations, we marinated it with the few spices we've come to recognize over here and I set to work on making the wonton wrappers. In America, you can find these bad boys at any Asian market. Around here? Not so much. Homemade from scratch it is!

All you really need for this is water, salt, and egg mixed nicely together before pouring it into the middle of a bowl of flour and some more water before you mix, mix, mix until it creates a nice dough ball. Wrap it and let it sit for 30 minutes. Once you've let it settle, it's time to bust out the rolling pin. Sadly, we didn't have a rolling pin or a wooden dowel so I improvised and used a wine bottle (I swear I'm not an alcoholic). It's a bit tough getting the dough as thin as it needs to be and after you're covered in flour and your hands are aching, you understand why you go out and buy these premade in America.

While I continued to roll and cut the dough into thin 3x3 squares, Adam began to fill them with our delicious mutton and eggs cooked in the mutton fat (trust me, it was more fat than meat). In the end, we had almost 30 dumplings to either steam or fry.

Since this was my master plan (at least in my head I knew it could work), I was in charge of cooking these little guys. Now, I'm the first to admit that I'm not the best chef in the world. Sure, I make a mean stuffed banana pepper soup but it's one thing going from a recipe and making stuff up as you go and hoping that it will all work out in the end. This had been hours of prepping, rolling, and stuffing... I couldn't mess it up now! No pressure...

Ignore our nasty little kitchen...

If the smell was any indication, things turned out better than I anticipated.

Low and behold! Our steamed and fried jiaozi turned out great (though they do kind of look like little turds) and they tasted even better.

Our first DIY of Bayannur was a huge success! But, I was determined to try something a bit harder and something I craved even more.

CHEESE

Cheese is just one of those things that you either love it or you hate it and I have a passionate love affair with it. The biggest downside of living in China (apart from being so far away from family) is the total and complete lack of cheese. I assumed that Bayannur might be a bit different from Hangzhou--dairy is actually a big part of life here in Inner Mongolia. You can find milk and yoghurt at every store you walk into but for some reason, cheese is still a myth over here.

So when I found cheesecloth at the night market, you can be darn sure I found a challenge on my hands.

Now cheese is hard because many of them require bacteria cultures which even if I could find over here I doubt I would dare use it in my food. But luckily, I found a recipe for Farmer's Cheese with just three ingredients: milk, white vinegar, and sea salt.

For anyone interested in trying this on your own, here's how we did it!

Pour one gallon of milk into a pot. It should not be super pasteurized and the pot should have a nice thick bottom. Sadly, we had to buy 15 little boxes of milk to get to a gallon... it should be easier in America!

Over medium heat, bring the milk to a boil. This takes a bit of time... It will start curdling on top so you should keep stirring it pretty frequently so it doesn't burn to the bottom. I thought I was stirring it enough but at the end I saw I had scorched it pretty bad.

As soon as the milk starts to boil, reduce the heat to low and add 1/2 cup of white vinegar. Almost immediately, the milk should start separating into curds and whey (I had no idea it was a greenish blue! Little Miss Muffet what is wrong with you?!?). If it doesn't, keep adding vinegar, one tablespoon at a time. It will be obvious when it starts working.

I'm not going to lie, I kind of lost it at this point. I started jumping up and down and shouting, "SCIENCE!" over and over again as the curds continued to form.

|

| My SCIENCE! face. |

At this point, the science part is done. Take your cheesecloth and line a colander with it and begin to scoop the curds out of the pot and into the cheese cloth. This kind of cheese is very crumbly and is in little pieces so make sure to get it all. You'll be surprised by how much cheese this actually makes!

Once all of the curds are in the cheesecloth, rinse them with cold water to get rid of any of the extra whey. Once they're nice and clean, sprinkle the sea salt on top. The recipe I used said two teaspoons, however, this cheese is pretty bland so I would recommend more (I'm even thinking of adding garlic or onions or little peppers the next time I try this). Once the curds are salted. tie the cheese cloth, squeeze it tight to get rid of any more whey and excess water and then you should find a nice place to hang it up! It is still a bit wet so we hung it up over our sink so if it dripped it wouldn't make a mess.

After two hours of impatiently waiting, we nervously opened up the cheese cloth and voila! Our very first attempt at cheese!

And this cheese is good for up to about a week!

I was surprised by how easy this was and how well it turned out on our first try. So far we're two for two in the DIY attempts here in Bayannur. I know sooner or later we're bound to fail miserably but for now I will happily eat my jiaozi and cheese and continue counting down the 82 days until I am drowning in good beer, burgers, wings, and cheese... so much cheese.

Until Next Time,

Amanda